The Story of…

Kendal Wool

From sheep to socks - a history of the wool trade in Kendal.

From sheep to socks - a history of the wool trade in Kendal.

Kendal Town Hall Door

Kendal's Motto is "Pannus mihi Pannis", which means 'Wool (or cloth) is my Bread'. You can see it carved over the entrance to the Town Hall.

This is the Coat of Arms of Kendal which can be seen on Victoria Bridge and clearly shows the elements which make up the shield.

Kendal Coat of Arms Victoria Bridge

A Bale Hook

Kendal's three surviving Mint cake manufacturers are Quiggin's, Romney's and Wilson's.

The other items featured on Kendal's Coat of Arms are teasels which were used to bring up the nap or fluff on the surface of the finished cloth.

Kendal's prosperity was built on the wool trade over many centuries, and the town became famous in the earliest times for its coarse hand-woven cloth, although later it produced fine cloth of many different kinds

A Teasel

Elizabeth I Charter

In 1575, Queen Elizabeth I granted Kendal a Market Charter and this is when the boom in the cloth trade really began making Kendal a rich and prosperous place

There was enough wealth coming in to the town to improve and beautify the Parish Church, which was originally built around the same time as Kendal Castle, in about 1210 to 1250.

The Parish Church

The Old Grammar School

Kendal's prosperity from the wool trade allowed a Grammar School to be endowed close to the church and provided numerous charities for the poor and needy.

The Bellingham family of Burneside were the greatest wool producers: you can see their chapel and the brass memorial to Alan Bellingham in the Parish Church.

Alan Bellingham

Sandes Hospital

In 1659, Thomas Sandes, a wealthy woollen merchant, founded the Sandes Hospital almshouses for poor widows, which still provide housing today.

This coat of arms at the entrance to Sandes Hospital almshouses shows a swag of cloth, teasel bats and shears.

Sandes Hospital Coat of Arms

Black Faced Sheep

Why did Kendal become so successful over the years?

There were several factors: great flocks of sheep, most of them the blackfaced breed provided a ready supply of fleeces.

Plenty of water was avaliable as well as an abundance of bracken for making potash to produce the soapy solution for washing the wool.

Very capable merchants and a ready supply of workers flocked to the town.

Winster Potash Kiln

Wool Processing Steps

The process of turning a sheep into a length of cloth is a long and laborious one. After shearing, the fleece was washed, usually in urine, to prepare it for carding.

This was done to ensure all the fibres lay the same way, using pads set with wire teeth.

Then the wool was spun and woven before being fulled in a soapy liquid to pound the loosely woven fibres tight.

Dyeing followed, with Kendal Green being the most well known colour. Since plant dyes were used, the colour was variable but was probably a rather dull green.

The surface of the cloth was brushed with teasels which were mounted on a teasel bat.

A Freizing Bat

Shearmen

Once the cloth was brushed it was either left fluffy or cropped short with very long shears by workmen known as 'Shearmen'.

Once the cloth was finished and washed, it was stretched to dry on tenter frames, which were set up all over the town.

Tenter Frames

Waterside washing steps

The river was used for washing wool and cloth.

Washing steps and platforms were built all along the Waterside; several have survived the centuries and were restored recently by Kendal Civic Society.

Robert Wiper handed the business on to his son, Harry, who continued to follow the original recipe and method of production that Joseph Wiper used over 100 years before.

A Weaving Loom used by Mr Dixon

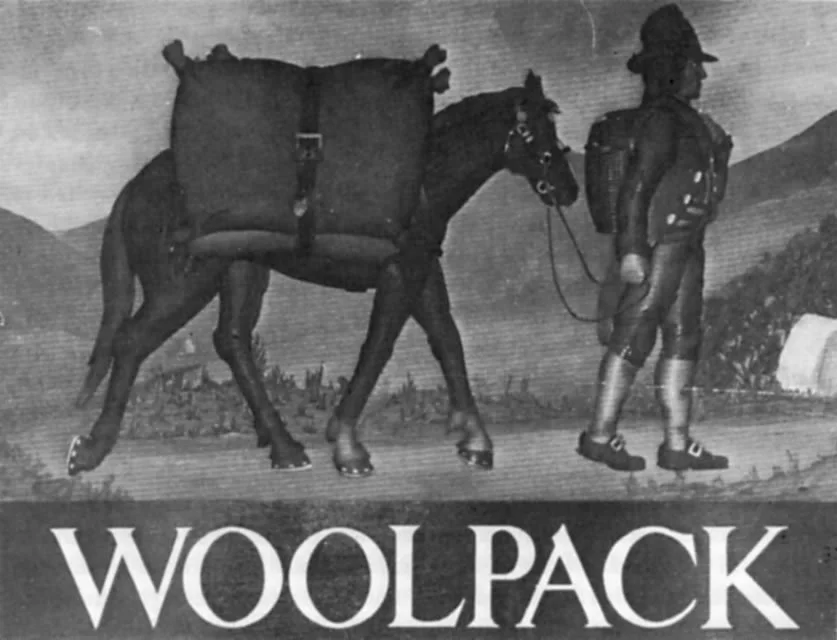

The Woolpack Sign

The cloth was carried by trains of Pack-horses to all parts of the country; in 1750, 214 pack horse loads left Kendal every week.

By 1787, great horse drawn wagons took over; it took 12 days for the eight horse teams to do the round trip between London and Kendal.

A Wool Wagon

A Dentdale Knitter

By the late 17th century, hosiery had become a major product.

Thousands of men, women and children were employed in hand knitting, in and around Kendal.

The yarn was supplied by agents who later collected the finished stockings.

This was hard work, poorly paid, but it made the difference between mere poverty and starvation for many families.

Many people knitted in every available minute, often using a knitting sheath to hold the needles.

In the 1770s, over 250 dozen stockings a week were sent out from Kendal.

Eventually mechanisation took over all this work of weaving and knitting, until the cloth trade began to die out in the 19th century.

There is little sign of the once great prosperous businesses now in Kendal.

A Knitting Stick

The Fleece Inn

The past still lingers on if you know where to look. The Fleece Inn's name being one of the most obvious signs of the wool trade in Kendal.

The Woolpack, with its great high arch to allow the laden wool wagons to pass beneath, still survives.

The Woolpack Hotel

An aerial photo of Kendal today

Here in modern Kendal, names such as Tenterfell, Dyer's Beck and Tenterfield are still in use.

And if your surname, or that of someone you know, is Webster, Mercer, Cropper, Lister, Bowker, Shearman or Sherman, and Walker, your ancestors were probably employed in the woollen trade which brought such wealth to Kendal. You are a living link with the past.